The Protein Transition: unchaining a revolution

With pioneering patents, leading start-ups, strong scientific research and the presence of industrial giants like DSM, the Netherlands has everything it needs to lead a revolution in the field of meat substitutes and cultured meat. Unfortunately, the legislation relating to these products is slowing things down and promising start-ups are moving abroad. Is our country at risk of falling behind?

By Jurjen Slump • April 6, 2023

According to Henk Noorman, a chemical engineer who works at both DSM and TU Delft, the protein transition (see box) will be a game changer. Agriculture, cattle farming and fishing will continue to be significant food flows but they produce too little to be able to feed a predicted global population of 10 billion people in 2050. He envisages the creation of a new flow of food, the bulk of which will be made by industrial parties.

These industrial parties will have factories with enormous bioreactors filled with microorganisms such as bacteria, yeasts, fungi or mammalian cells. They will produce protein for meat substitutes or animal feed and they will also make cultured dairy and meat products that are indistinguishable from the real thing. The ingenious thing about this is that you can use greenhouse gases (CO2) and other residual products from the chemical industry (nitrogen and hydrogen) as food for these single-celled organisms.

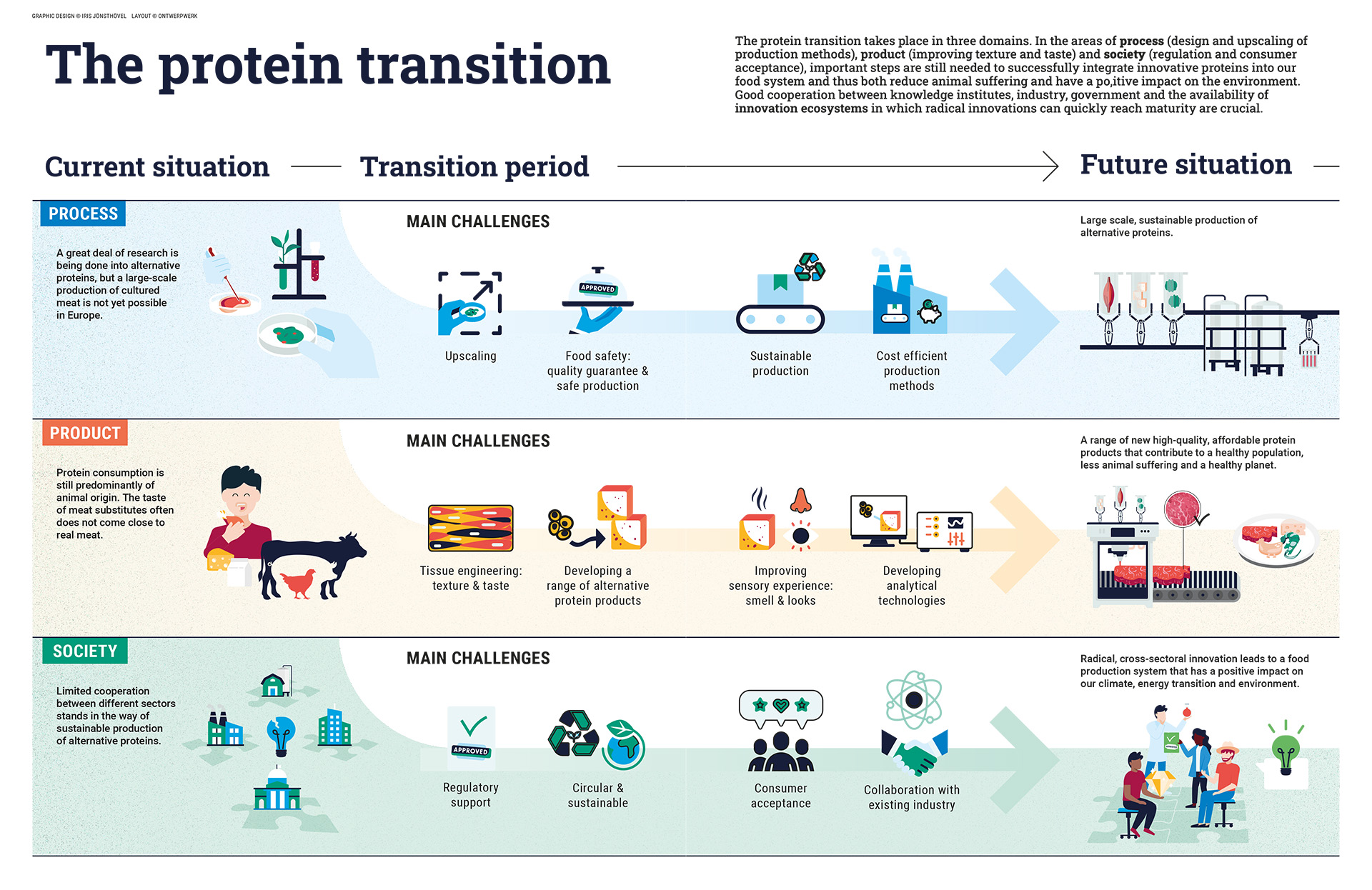

Protein transition

In addition to fat, carbohydrates, vitamins, minerals and fibre, we need protein for a healthy diet. Protein is primarily found in meat, fish, eggs and dairy products. The problem is that scarcity is looming because of the expected growth in population to 10 billion people by 2050. Besides which, cows are polluters par excellence – they release CO2, methane and phosphate – and anything but efficient. A cow has to eat 20 kg of vegetable protein to produce 1 kg of animal protein (meat).

Overfishing leads to empty seas, and the production of vegetable protein (particularly soya) leads to deforestation, with all its ecological consequences. This is why solutions under the heading of ‘protein transition’ are being sought in numerous places all over the world. These solutions vary from the cultivation of typical, local Dutch protein-rich crops, such as field beans as alternatives for soya, to technological innovations in the form of meat substitutes and cultured meat. The production of these meat substitutes and cultured meat takes place in bioreactors. This is considerably more efficient and prevents a lot of animal suffering to boot.

Self-sufficient megacities

Another advantage is that the easy scalable protein production will enable megacities and densely populated areas, such as the Randstad, to be self-sufficient. “This would deliver an enormous efficiency boost because you will need far less land and sea to produce the same quantity of products”, Noorman explains. This is one of the reasons why the city-state of Singapore was one of the first countries to allow the production of cultured meat.

The protein transition interlocks with everything: it contributes to solutions for the climate and nitrogen crises, energy transition, overfishing, lack of space and nature restoration.

“It is important to drive innovation if we are to make any societal impact”

Cindy Gerhardt, Managing Director Planet-B.io

Radical innovation

Moreover, it forces the established industry (chemical and energy companies) to search for totally new business models. “Innovation primarily takes place on the boundary between two sectors that go into partnership. That is where the power lies”, says Noorman. “The joining of forces of the traditional chemical industry and companies that make food with innovative proteins will bring about great change.”

The outlines of this future are already visible in Delft. Eighteen start-ups have been set up at Planet B.io on Biotech Campus Delft’s site, more than half of which are engaged in the protein transition. One of them – Deep Branch – has developed technology that uses microorganisms, which can be fed on CO2, hydrogen and oxygen, for the production of animal feed. Last year, another well-known company – Meatable – unveiled the first sausage and dumpling made from cultured meat.

It is no coincidence that these companies have chosen to locate here, says director of Planet B.io Cindy Gerhardt. Planet B.io provides laboratory space for biotech start-ups and scale-ups and is building up a local, regional, national and international network of expertise in the field of biotechnology. It also connects DSM’s knowledge and experience with the research carried out at TU Delft and links it to start-ups. Gerhardt: “We have the whole ecosystem together here, which is an invaluable situation. It is important to drive innovation if we are to make any societal impact. Delft is particularly strong in this. We don’t just discover things, but we also subsequently scale them up and roll them out on a global scale.”

Scaling up processes

“The technological developments in the field of microbial protein (produced by bacteria, yeasts and fungi) are advancing at an amazing pace”, says Jack Pronk, Professor of Industrial Microbiology. Scientific research is focusing on scaling up biotechnological processes. “We link our know-how regarding large production processes to in-depth knowledge of how microorganisms function under different conditions.”

In fact, there is quite a difference between how bacteria grow in their natural environment versus in a big bioreactor. “If you want to culture these ‘beasties’ on a very large scale, it entails having them perform under conditions that they do not encounter in nature. This is a tremendous challenge for biotechnologists”, says Pronk. “We look at the situation from the perspective of a biologist and an engineer.”

The National Growth Fund

Cellular agriculture, as it is known in the jargon, has a unique position in the protein transition. This concerns meat that is directly cultured from animal cells or dairy products made with the aid of microorganisms, for example. In both cases, the cells produce the same animal proteins and fats. In addition to Meatable, MosaMeat is another prominent player. Based in Maastricht, it created the first cultured burger in the world in 2013. Cellular agriculture is not limited to meat and dairy products; it can also be used to culture fish and leather.

This year, the National Growth Fund has pledged 60 million euros to accelerate research, teaching and innovation in this field (see box). Marcel Ottens, Professor of Bioprocess Engineering, laid the foundations for this work.

Growth Fund

Last year, the National Growth Fund pledged an investment of 60 million euros. This money was applied for by a consortium of 12 parties, including three universities, DSM, Planet B.io and a series of start-ups.

The funds will be used for setting up open, accessible scale-up facilities for start-ups and scale-ups. There is also a teaching and research programme at the three universities in question: TU Delft, Wageningen University & Research and Maastricht University. Delft is focusing on cell culture, Wageningen on precision fermentation (the production of proteins by microorganisms) and Maastricht on tissue engineering (the texture of the cultured meat). The consortium is also working on the social acceptance of cellular agriculture.

Economically viable

“In the pharmaceutical industry, animal cells have already been cultured and used to make vaccines or medicines, but that involved much smaller quantities of cells that were not intended to feed the world”, says Ottens. If you are going to scale up, you face a number of limits.

The challenges are varied and include the reactor (fermentor), process design and affordable food (medium) for the cells. “We look not only at how to design a good reactor and process but also at the entire chain around them.” The whole thing must be economically viable too. “Techno-economic analyses are very important; we can design a new process with a suitable reactor for large-scale production, but it will be useless if it does not yield a profit.”

As the innovator of cultured meat, with the Dutch getting the first patent for it, Noorman, Pronk, Ottens and Gerhardt all agree that the Netherlands has all the right ingredients to play a key role in the protein transition. But there is one huge obstacle. Whereas microbes for food (e.g. yeasts and yeast extract, food fungi, lactic acid bacteria) have been on the market for some time now and new related products are approved fairly quickly – for applications such as fish and cattle feed, a report in retrospect suffices – legislation does not yet allow the marketing of cultured meat.

This is why Meatable will be opening its first factory in Singapore in a couple of years; Singapore already allows cultured meat, as do the United States of America and Israel.

Dumplings and little sausages

“We would naturally have liked to start in the Netherlands but, because of the legislation and regulations in the EU, that’s going to take a while”, says Daan Luining, CTO of Meatable. In the coming years, Meatable is going to launch the first cultured pork, most likely as dumplings and little sausages, on the Singaporean market together with a local manufacturer.

From an innovation perspective, it is incredibly important that Meatable market its products in Singapore. “We are ready for the next step”, says Luining. “We know how to make meat but it is now very important that we can taste it and continue developing the products.” Feedback from consumers yields indispensable information.

Little urgency

He is supported by D66 politician Tjeerd de Groot, who is promoting cultured meat in the House of Representatives. The fact that Meatable is diverting to Singapore is good news and bad news. “The good news is that this company can finally start to earn money, which is unbelievably important for start-ups. But the bad news is that those in Brussels are not aware of the urgency of having this type of significant innovation mature in Europe.”

De Groot is astounded that Brussels is dragging its feet on this. “Cultured meat is manufactured under far more hygienic conditions than meat from an average abattoir”, he says. The D66 representative demands that the cabinet get cracking in Europe. “This should be at the top of our list of priorities.” He also wants the government to enable tasting sessions – sooner rather than later. A motion to this end was adopted last year but the Minister of Agriculture has so far not been in too much of a hurry to implement it.

“Every food business that launches a new product on the market first wants to know whether consumers like it. And in the case of cultured meat, this is really important.” What is more, tasting sessions can help stimulate social acceptance of cultured meat.

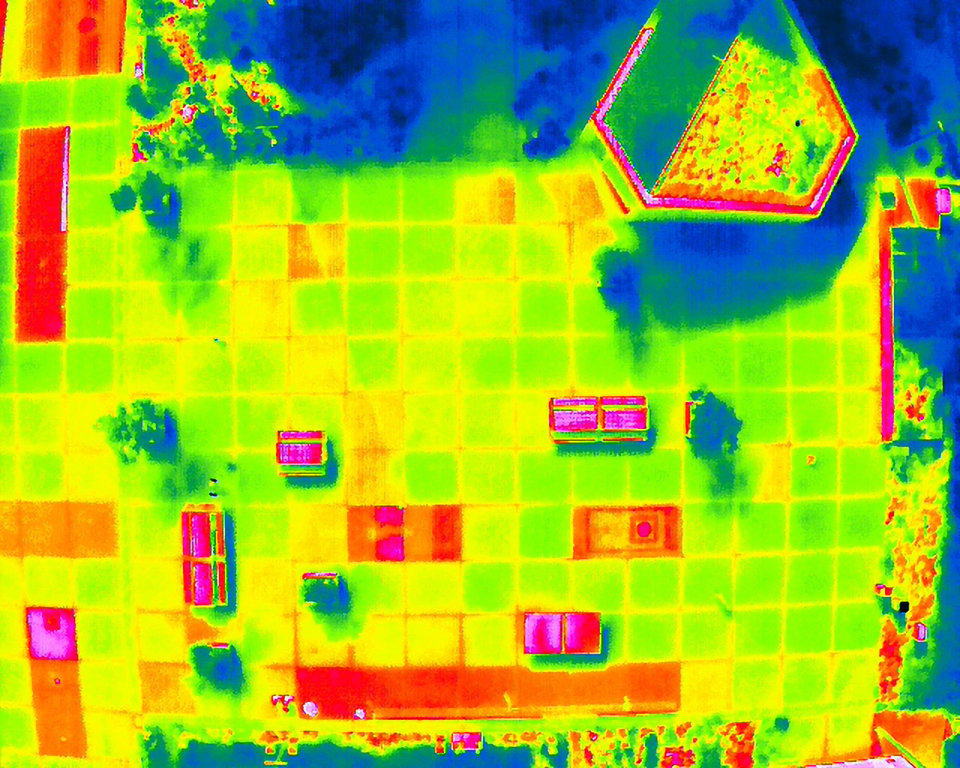

Neutrons used as alternatives to tasting sessions

The right ‘mouthfeel’ is an important aspect of getting meat substitutes accepted by the general public. Tasting sessions are useful to this end, but TU Delft is also carrying out research into alternative methods of measurement. At the Reactor Institute, neutrons are being used to map the texture of meat substitutes.

Big steps

Although legislation in the field of cultured meat is still slowing things down, the Netherlands could become a pioneer. Ottens expects big steps to have been taken in terms of reactor technology and the production process over the coming eight years. The money from the Growth Fund will lead to a completely new sector in the field of cultured meat, says Gerhardt. “Hopefully with a large number of innovative start-ups around it.”

Perhaps the most important aspect is acceptance by the general public. It has to taste good and be affordable. Pronk thinks that the flavour of meat substitutes made with microbial protein will only improve. And if it can be produced more cheaply too, things could start to move very quickly.

Luining expects the prices of Meatable’s products to be comparable with those of traditional meat once they can be produced on a large scale. He is also confident as regards the acceptance of it. “Give people the choice between cultured and conventional meat, including information on the impact of the two types on the environment. If consumers cannot tell the difference between the two when it comes to flavour, we are confident that they will incorporate cultured meat in their diet.”