The self-driving car is on its way. Or is it in fact already here? In June 2017, Transport Minister Melanie Schultz van Haegen opened the Researchlab Automated Driving Delft (RADD) on the TU Delft campus. In the lab, automated driving experiments are being conducted under the supervision of Professors Bart van Arem and Dariu Gavrila.

In 2011, there were an estimated one billion cars worldwide and that figure is expected to have doubled by 2035. These huge figures encapsulate a number of reasons why automated driving seems to be a good idea. First of all, for safety reasons. Every year, there are 1.2 million traffic fatalities worldwide, most of them caused by driver error. “There is an awful lot that can go wrong behind the wheel,” says Dariu Gavrila, Professor of Intelligent Vehicles in the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering (ME). Then there are the congested roads and city centres grinding to a halt. “A great many cities would benefit from a combination of car sharing and automated driving in order to improve quality of life in city centres,” adds Bart van Arem, Professor of Transport Modelling in the Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences (CEG).

But the question is when exactly this will happen. Rather than a revolution, it will be an evolutionary process, which has in fact already started, albeit slowly. “There are lots of people who don't yet realise that automatic systems already exist for your car,” explains Van Arem. “For example, there is adaptive cruise control that ensures you maintain sufficient distance from the car in front. Although it was introduced by Mercedes and Jaguar back in 1999, only 10% of all new cars have it so far. We expect the introduction of systems of this kind to accelerate, partly because insurers have noticed they result in reduced involvement in accidents and related damage.”

Gavrila does not have a ready answer either, although he expects it will take another 10 to 15 years before self-driving cars really have an impact on traffic: “The level of penetration first needs to be sufficiently high.” Ultimately, the self-driving car will actually be much better than the human driver. “If it turns out to be a hundred times better, you will start to wonder whether wanting to continue to drive is not anti-social,” he argues. Gavrila foresees the same future for manual driving that previously befell smoking. “Smoking used to be sexy and a symbol of freedom. We then found out that it was unhealthy, for yourself and those around you. Then the tax on it was increased and it was eventually outlawed in many places. That tipping point will also eventually come for self-driving.”

In any event, a lot of hard work is being done in Delft to make it possible. Van Arem is working at the level of the entire transport system: “We are looking at how automatic vehicles can develop within the existing system. What impact will they have on traffic congestion, for example,” he says. Gavrila is focusing on perfecting the vehicle itself. “Currently, people are still better at judging situations than vehicles are,” he says. “Machines need to learn to anticipate instead of just react.”

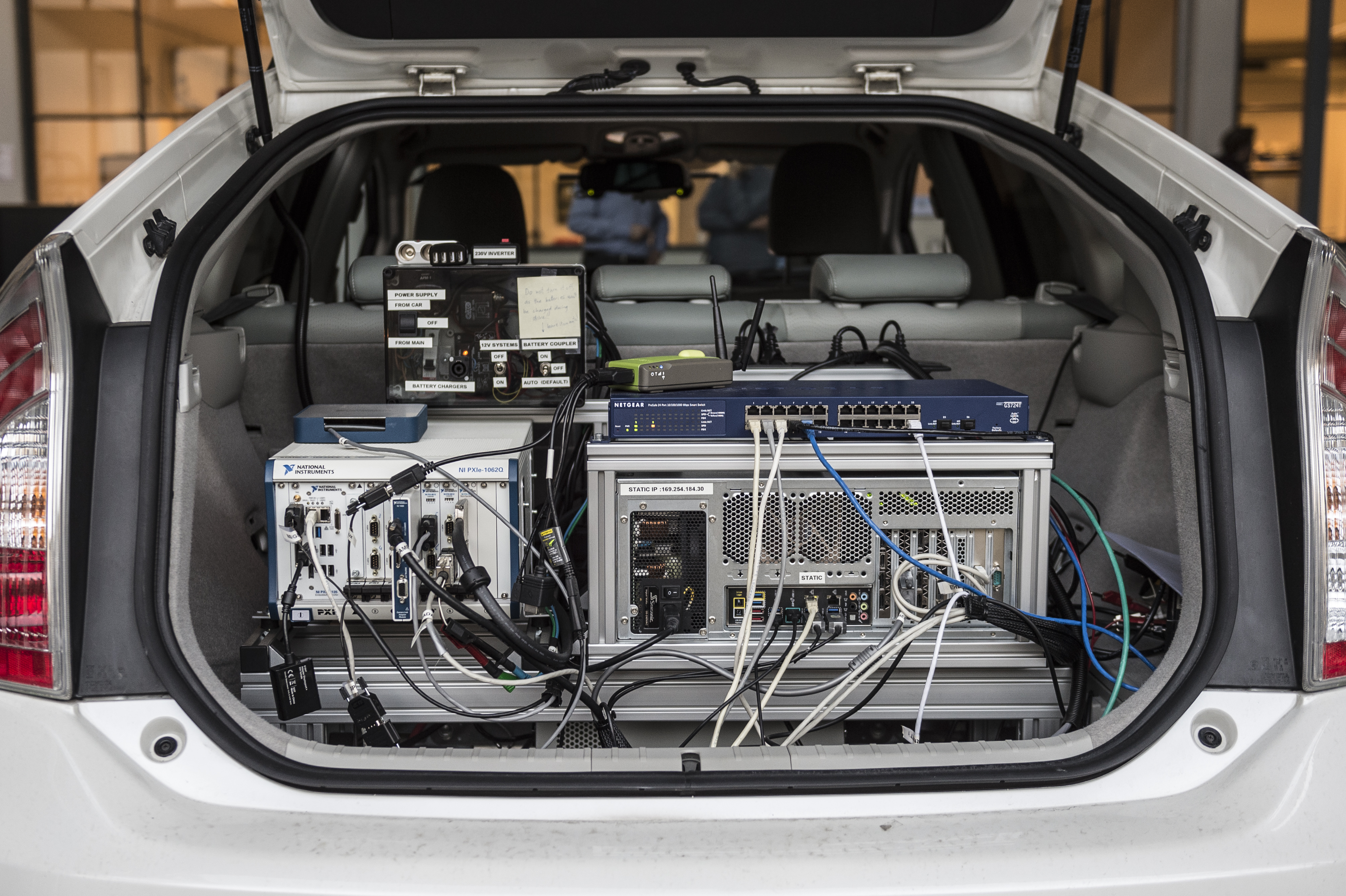

This is where both specialist fields converge: in the Researchlab Automated Driving Delft (RADD) on the TU Delft campus, experiments are being conducted with automated transport in real-life situations. “There is a limit to what you can do on a computer,” says Van Arem, one of the initiators of the lab. The RADD has access to two Toyota Prius and a WEpod shuttle vehicle from the Province of Gelderland. As well as on the designated test site on campus, pilot projects can also be conducted on public roads and on and around the campus. “We can use these to investigate how vehicles interact with cyclists and pedestrians, for example.” The campus will also be equipped with sensors that can test communication between vehicles and infrastructure.

Read the full interview in the Portraits of Science booklet of Delft University of Technology (January 2018)