What would you do when invited to explore an abandoned concrete factory?

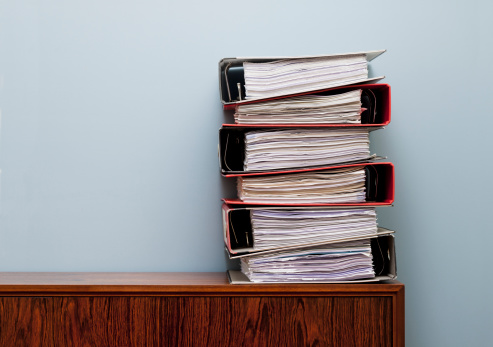

In 2015, Dr Wido Quist, associate professor of Heritage and Architecture, was advised to promptly pay a visit to the bankrupt Schokbeton in Zwijndrecht. On arrival, he found hundreds of different concrete tiles, one thousand recipes for concrete, and huge folders full of visual material. Wido and his colleagues took as many photos and scans as possible, and even took some materials with them. Why? "Firstly, we are saving unique knowledge about the history of architecture. And secondly, this archive holds a key to the sustainable preservation of our built heritage."

Concrete, a mixture of sand and gravel with cement, is the second-most consumed material in the world after water. And popularity brings criticism. Nowadays, concrete is almost synonymous with ugly and uninspired. Not so with Wido: ‘Drop me in any city and I can tell you all about its concrete architecture. The Holbeinhuis in Rotterdam contains red brick dust, Zutphen railway station is full of flint, the white concrete of the former Banque Lambert in Brussels is polished smooth... All these are deliberate choices by designers and builders!’

It is therefore a coincidence but not a surprise that Schokbeton crossed his path.

From Dutch pride to unwanted child

Schokbeton emerged in the 1930s, specialising in thin, aesthetic walls and building elements... made of concrete. How did they do it? As the name suggests, it's a matter of hitting the moulds with hardening concrete. These ‘shocks’ remove air bubbles and cause the mould to fill perfectly. Wido: “According to the story, the inspiration was an employee who was transporting concrete with a broken wheelbarrow. That seems exaggerated to me: the consequence of kicking against moulds was common knowledge.” But Schokbeton made machines that could perform the process on a massive scale.

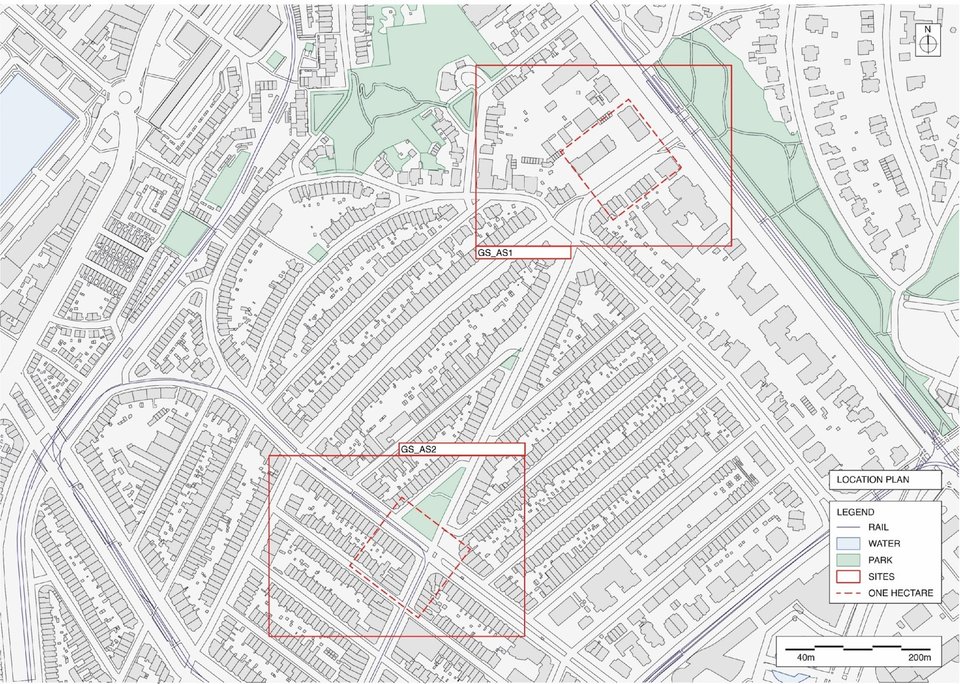

Their timing proved very favourable: after World War II, Schokbeton could barely keep up with demand. They became the largest in the Netherlands, supplying thousands of different building elements to homes, offices, and even farms. The company spread its wings internationally: barracks for the US army in Greenland, the Peugeot headquarters in Paris, the US embassy in Dublin... Wido: "If you look closely at the styles and colours of their buildings, you can see that a lot of love and attention went into them. Schokbeton often designed a new concrete mix for a single project!"

But these golden days could not last forever. Architects of the 1970s switched to heavy, load-bearing facades, which made the thin elements and special techniques of Schokbeton redundant. They tried experimenting with brutalism and tiled walls, and got a few more major commissions: the Peeperklip and Willemswerf in Rotterdam, the academic hospital in Utrecht... Wido: ‘I found an ambitious project in their archives: an entire residential neighbourhood in Saudi Arabia! Thousands of concrete elements were shipped, but it didn't generate enough revenue." After a string of new owners, Schokbeton was forgotten.

What we can learn from Schokbeton

Thus we are back at the beginning: Wido and colleagues at an abandoned factory site. Why are they going to all this trouble to rescue knowledge from a defunct company? There are three answers.

1. Restoration is more sustainable than rebuilding

Producing concrete requires a lot of non-renewable resources and emits a lot of CO2: in other words, not exactly climate-conscious. But with existing concrete structures, the ‘harm is already done’. Wido: ‘That is why we need to preserve or reuse all these supposedly obsolete buildings as much as possible.’ Schokbeton's archive teaches us how to repair existing structures. A much better option for the environment than demolishing, which generates a lot of waste, and building something new, which creates CO2 emissions.

2. Concrete heritage is cultural heritage too

Taste is subjective and constantly changing. Right now, concrete behemoths are not fashionable, but "destroying our concrete heritage for that reason is doing a disservice to future generations." Wido sees two solutions. "First, draw attention to these buildings. After all, unknown makes unwanted. Second, adapt buildings to current needs." And since a lot of this heritage exists because of Schokbeton, studying their techniques and types of concrete helps with both approaches.

3. Old techniques, new applications

Concrete is increasingly seen as the ‘black sheep’ of construction due to aesthetics and CO2 emissions. Yet it remains hugely popular. After all, concrete has important advantages: it is cheap, versatile, robust, and long-lasting. If we are going to continue constructing with concrete, then let's do it right. The thin elements of Schokbeton were more about aesthetics at the time, but they are also resource-efficient. Wido: “If we re-learn to apply those techniques, we can optimise structures where concrete is really needed.”

Cease your demolition!

Wido's core message is really quite simple. Concrete is going to last, so let's commit to reuse. “If we understand the financial, cultural, and historical value of concrete heritage, we will naturally come up with the best ways to renovate, restore, repurpose... This is how you really make a difference for the environment.” With his research, Wido is doing his bit, but he cannot do it alone. “We need a government that is much stricter with demolition permits: demolition should be the last resort.” Designers and architects (in training) also need to be challenged to work with what exists. And to everyone, Wido says: “Learn about concrete! The history, the applications, the potential... Look around you, consider what you already have; you will soon see possibilities."

This story is published in September 2024.

More information

For the use of any of the images in this article, please contact Wido.

Read more about the history and influence of Schokbeton in Wido's comprehensive and freely accessible publication.

Read more about recent built heritage (1975-2000) in this collection of summarised publications.