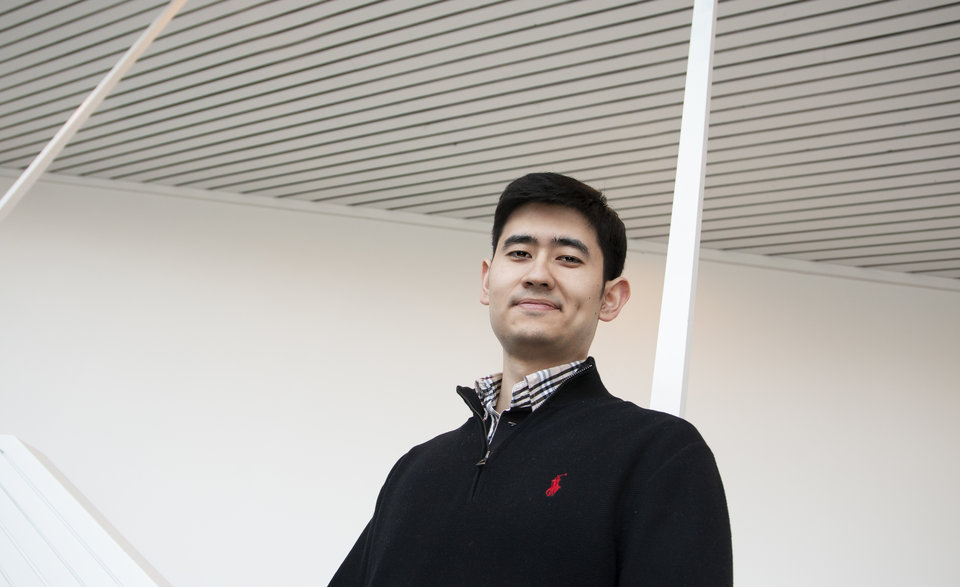

Forty-five minutes of stress in a sea container that has been transformed into an infrarium filled with physical and mental challenges. How do you go about laying energy cables without disrupting industry or energy suppliers? How can you work with others in a small space filled with smoke, flashing lights and incessant noise? What effect do stress and emotions have on decision-making? The Energy Grid Game simulation reveals the challenging decisions that the energy sector will face during the current energy transition. This case focuses on the Port of Rotterdam. The game was designed by Igor Nikolic, associate professor of participatory multi-modelling, and Geertje Bekebrede, associate professor of serious game design. The goal is to allow participants to experience, both physically and emotionally, the urgency, cohesion, mutual dependence and complexity of the energy transition.

A sea container looks large on a lorry but turns out to cramped and claustrophobic once you’re inside with the doors shut. It’s brimming with used and reconditioned equipment, cables, plugs, wall sockets, sirens, lights and system walls. Nikolic: “The game replicates elements of the industry and energy supply of the Port of Rotterdam. The models and the data are derived from real-life projects such as Windmaster and Gridmaster in which we work on models for investment strategies in the energy sector. This adds realism to the game.”

The sea container can easily be transported by truck to the head office of TenneT, for example. Company directors can play the game on-site. “Then I can drive on to a university of applied sciences. Are students better at the game than directors? Quite probably!”

Models for a sustainable world

Computer models, cables, pipes and energy transition – an odd combination? “Not to me. I’ve been playing with computers and doing programming since I was very young. During my chemical technology studies I experienced the huge environmental impact of chemical technology for the first time. The more I learned, the more impressed I became with the gravity of the situation. I also started to appreciate the complexities of understanding the situation and the search for solutions. In my present position, I can combine my interest in computers and modelling with the sustainability challenges that we are facing. The social scientists at the Faculty of Technology, Policy and Management (TPM) have helped me to appreciate the importance of understanding irrational, illogical and occasionally crazy group behaviour. It suits me to make this shift towards the social aspects of the modelling of sustainability problems: I want to use my creative brain and my skills as a maker of tools to contribute to the tackling of worldwide sustainability issues. I want to be on the right side of history in this respect.”

Wicked problem

Investment choices for future energy provision involve great expense and have a long-term effect. These decisions are taken under conditions of enormous uncertainty. “It’s a wicked problem, a problem without a universal, uniform definition and a problem about which we can only be sure that we will never fully agree on any single potential solution. In addition, energy infrastructure projects are highly expensive and laborious. Besides the technology and the objective facts, the experienced quality, values and standards of those concerned also play a role. The solution offered for a minister’s approval is being developed by a very small group of people. My estimate is that there are between 50 and 70 people at the grid operators, transport operators and energy providers in the Netherlands who are involved in long-term planning. It’s important to me to understand what the role of the individual is in such a complex decision-making process. What goes on in their minds? How are they influenced by the world around them? These are rational people who calculate everything, on the basis of numbers, graphs and their own models. But there is also an important emotional component. If we can understand the influence of emotions and stress on the decision-making related to such large, complex and abstract problems, we can then develop better social processes, modelling, and institutional facilities. This will eventually lead to greater tolerance towards, and acceptance of, the energy transition.”

Transdisciplinary

During the lockdown, Nikolic had a conversation at the faculty with his colleague Geertje Bekebrede: “She was frustrated by the fact that the lack of in-person contact during the lockdown was having a negative effect on students’ results and was making research projects more complicated. This chance encounter was the moment when the idea for a physical game was born: No paper, game board or computer, but a physical and interactive game that communicates with you: an infrarium. The participants experience for themselves the complexity of the infrastructure system, and they feel the pressure, the tension and the relentlessness of decisions. How do the minds of decision-makers work and how do they arrive at their conclusions? As a handyman, I enjoy the development of a physical game that you can construct with your own hands. My office is scattered with homemade tools and to me that illustrates an important role that we play as a university: improving tools to help those involved to gain more comprehensive insights that in turn lead to more sensible and useful decisions. The quality of our TPM faculty is derived from this combination of technological science and insights gleaned from social and humanitarian disciplines.”

Who fails least?

The Energy Grid Game is played by three players with different roles and interests. For example, a harbour master, a factory manager and the manager of an energy company. They have to arrive at decisions on how to design the energy infrastructure. The panels in the container represent factories, and the participants have to lay heavy cables and secure them with large couplings. It is hard to collaborate and to pass things to each other in such a small and dark space. The participants experience the physical restrictions of working underground. This is similar to the full underground infrastructure of the Port of Rotterdam. If you have chosen a cable that is too short, you have to rectify your mistake quickly: it is very expensive because a factory is rendered idle in the meantime. You have to make decisions while under pressure and suffering from stress and physical discomfort, and you have to live with the consequences of your decision. The smoke may become thicker, indicating that your CO2 emissions have increased. Everything you may or may not do has consequences. Have you opted for the wrong energy source or laid the wrong cable? You cannot easily go back because you’ve used up a few billion in the process, and you have a shortage of technical staff to set things right. It’s getting hot and there is a lot of noise and it’s hard or impossible to communicate with each other. Your thought processes change and you’re afraid to make mistakes that cause others to suffer while suffering yourself from their mistakes. “This is a game that you can only lose. The trick of it is: Who fails least? It is not an escape room, because there is no solution. It’s all about the process and the physical experience: the solutions you come up with are either less bad or marginally better than others. The participants experience the urgency, complexity and the mutual dependence of the energy transition in a physical manner, as opposed to the intellectual sense that they are accustomed to. Physical sensations are internalised at a deeper and more emotional level. The game results in a more profound understanding of these complexities and this leads to designs and investment decisions that take interaction and interdependence better into account. And, in the end, a better integrated and coordinated infrastructure system is simply more sustainable.”

Emotional and physical experience

Nikolic and Bekebrede hope that a number of conclusions will remain in participants’ minds once the game is over. “The players experience cohesion and mutual dependence: a small, random decision can have a tremendous impact. The urgency of the problem should also be evident. Everything that you do now will have an impact on 2050. That sounds a long way off, but you have to do the right things, or rather the least bad things, today. The physical nature of the game ensures that they leave the container with an emotional experience that cannot be had with an intellectual game. A fundamental problem with the whole sustainability discussion is that it remains so abstract and ‘distant’. When you play this game, you receive the message at an emotional and physical level. Yes, it’s a complex business, but we really have to get together now and take action on climate change. The game encourages focus, the pooling of expertise and decisive action.”

The premiere of the Energy Grid Game is on 8 October.

A game brimming with research questions

The game is a rich research project for various disciplines

- Game design

How can you create this type of physical game where the physical experience is integral to the learning process? This is under-represented in game literature. “You have to be aware of very different design components, such as physical safety during intensive assignments.” - Affective computing

How can you link (wrong) decisions to the emotional state of the players? How do people react to certain events? Our TU colleague Dr Iulia Lefter researches affective computing, the branch of artificial intelligence where machines observe people and attempt to gauge or guess at their emotional state. This is already in use for the training of the personnel of prisons and psychiatric hospitals. The game players are supplied with wristbands that can measure biometrics such as heart rate, skin response and temperature. The container is fitted with high-quality, high-resolution cameras that perceive facial expressions through the noise and smoke to provide extra data for analysis. These insights should lead to more effective designs of the social processes that influence the energy system.