Due to changing regulations and the introduction of feed-in tariffs, households with solar panels are increasingly required to use the energy they generate directly. Shifting energy use to other times — also known as load shifting — demands a change in behaviour. In her PhD research, Mariëlle Rietkerk investigates how willing households are to adjust their energy consumption and how hassle stands in their way. She incorporates her insights into behavioural models to provide a more realistic picture of what works and what doesn’t.

It has become increasingly difficult for solar panel owners in recent years with the uncertainty about whether or not the net metering scheme is scrapped and with energy suppliers introducing costs for feeding electricity back to the grid. Inconsistent government policies and issues with an overloaded power grid, known as grid congestion, mean that generating your own electricity is becoming less profitable. To use energy efficiently and cost-effectively, households need to shift their energy use to times when their solar panels are producing a lot of energy, says PhD candidate Mariëlle Rietkerk. “This shifting of energy use is also known as load shifting.”

Hassle hinders behavioural change

For her PhD, Rietkerk is researching the barriers that solar panel owners face when trying to adapt their energy use behaviour, focusing on what she calls 'hassle'. “I’m still defining this term precisely, but when it comes to load shifting, people need to change well established habits.. For example, charging their electric car or running the washing machine or dishwasher at a different time of day. This habit change can be a hassle because people might have less time during the day or suddenly need to keep track of when their solar panels are generating a lot of energy. Ultimately, my research is about how hassle limits the necessary behavioural change.”

Various influences on choices

Rietkerk has a background in psychology, graduating from Leiden University ten years ago. After her studies, she worked at TNO and Milieu Centraal. At TNO, she advised governments on using behavioural insights in policy. At Milieu Centraal, she applied her knowledge to help consumers make more sustainable choices. “I find it really interesting how people’s behaviour is influenced in so many ways. For example, by their immediate environment, the information they take in, but also their own beliefs. All these influences on decision-making are often overlooked in policy models, which tend to assume a more rational view of human behaviour. If we do A, it automatically leads to B. But that is not how it works in practice. I thought it would be interesting to explore this further. When my supervisor, Gerdien de Vries, whom I knew from a previous research project, had a vacancy in this area, it didn’t hesitate to apply.”

A more realistic view of behaviour

When policymakers do consider including behavioural insights in models, they often do so insufficiently, says Rietkerk. “There is no behavioural analysis behind it, and assumptions about behaviour in the models are rarely tested through experiments. For example, if people perceive hassle or not is modelled in a very general way. But you do not know which kind of hassles they perceive exactly. Whether they see it as a minor or major hassle, and what other barriers stand in the way of a behavioural change. So there’s a lack of depth in the models. Hassle is a broad and grey area. I hope to make it a more well-defined topic in my research, so we can differentiate between individuals and groups and distinguish different types of hassle. When a model has more detail, the outcomes also become more realistic. And you need that realism to create effective policy.”

Adding more detail to models

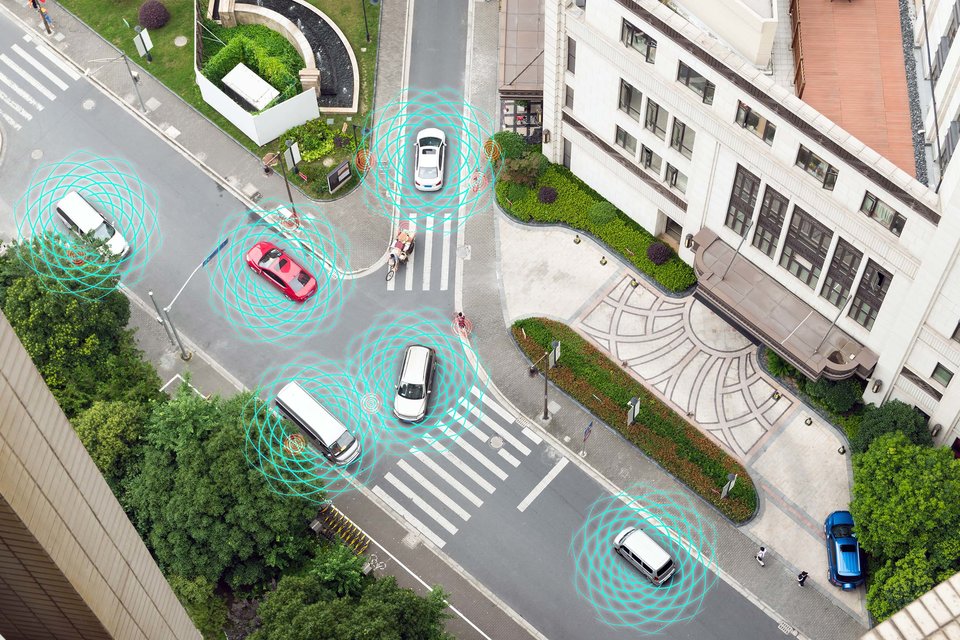

To add more in-depth knowledge of behaviour into models, Rietkerk uses Agent-Based Models (ABMs). “In an ABM, you can incorporate different types of hassle, but also other factors that influence behaviour, such as changing energy policy or information from peers, media or energy suppliers. By running such a model, you can see how those factors interact. What’s great about a model compared to, say, a behavioural experiment is that it shows results on a system level, and you’re not ‘stuck’ with results on the level of specific groups or individuals. Initially, my ambition was to develop an entirely new model, but I will likely focus on refining and adding detail to existing models.”

Uncharted territory

Rietkerk admits that modelling isn’t something that comes naturally to her. “I spent a large part of my first PhD year figuring out how models work and how to develop them. I underestimated how complex that really is. That’s why I’m working together with modellers. Embedding behavioural components in load-shift models is still uncharted territory. This is because load shifting is a relatively new topic for households. At the same time, the hassle factor limiting energy behaviour is scarcely explored in psychology. So, there’s work to be done both on the technical side — modelling — and on the social sciences side. I hope to fill those gaps.”

Mapping the hassle of load shifting

The second part of Rietkerk’s research — which she is currently working on — is more within her comfort zone. “I’m now collecting data. Recently, I asked 3,000 customers of energy company Eneco who own solar panels how much hassle they experience to run their washing machine at a different time, for example. I’m also going to conduct field experiments. This means I will visit people’s homes to see if we can reduce hassle through a specific adjustment. Think of an app or device that gives a signal when there is a lot of solar power available, or that allows you to control an appliance remotely when you’re not at home. I want to know if this really leads to behavioural change and if people find it convenient. For some, adding more technology to their homes is just another hassle.”

Ambition to change the world

Through her research on behaviour in the energy transition, Rietkerk ultimately hopes to contribute to a more sustainable world. “That drive to make a societal impact became clear to me when I was still working as a chemical engineer at a research institution. I came up with a solution that made separating certain liquids more efficient and therefore more sustainable. But when the industry scaled it up, the environmental benefits were lost. It turned out the industry was mostly interested in the financial benefits of the technology. That’s when I realised: if I want to change the world, I shouldn’t start with molecules, but with people.”

Looking for the right tools

Ultimately, better insights into human behaviour can help in deploying the right tools. “These tools can come from governments, such as regulations or subsidies that make solar panels more attractive, but also from the industry. The energy sector can, for example, develop products that help people with load shifting or energy-efficient behaviour. Manufacturers of electrical appliances and vehicles can also help. For instance, by making it easier to pre-set devices to use electricity when the sun shines. That saves hassle, too. This clearly shows that the energy transition is a process in which we all need to play our part.”