Battling the data hunger of Big Tech

Devices like smartphones and laptops have become indispensable in our daily lives. By using them, we share vast amounts of data, such as photos, personal information, and location details. Despite protective legislation, large tech companies have increasing control over how data is gathered and processed, expanding their power. TU Delft researchers Seda Gürses and Lilika Markatou are working to expose the practices of Big Tech and develop new privacy protocols and systems to curb this power and better protect users.

Big Brother is watching you. This famous slogan from George Orwell's dystopian novel 1984, written in the 1940s, remains relevant today. While Orwell referred to government surveillance through cameras, today tech companies show insatiable hunger for data, and intrude into our lives via services running on devices like smartphones, laptops, and smart speakers. What has changed over the last years is that the computational infrastructure to run these data-hungry services is now concentrated in the hands of a few companies, says Seda Gürses, computer science and privacy engineering researcher at the faculty of Technology, Policy, and Management. “There are really only four companies that have immense infrastructural control: Amazon, Microsoft and Google for clouds, and Google and Apple for smartphones. Together, they wield enormous power.”

Cloud as a production environment

These tech companies don’t just offer cloud services for data storage but also as a production environment. Gürses explains: “In this environment, engineers and developers use data to develop or improve software. The problem is, the more the environment supports them in doing their tasks, the less developers are able to decide how to handle user data privacy in the design; to ease developer’s tasks, this environment increasingly makes those decisions for them. When I first realized this a few years ago, it was an eye-opener. I saw how big tech companies moved on from a business model based on profiling users for targeted advertising, to selling a production environment to businesses and governments. These companies may now even introduce privacy measures and minimize data collection to entrench this environment.”

A protocol for privacy preserving contact tracing

While developing a privacy protocol for contact tracing during the Covid pandemic, Gürses saw that this aspect of big tech’s power became became visible to the public. “In contrast to proposals for digital contact tracing from start-ups, in the protocol we designed – DP3T – privacy of individuals was central. Contact tracing requires that you keep record of if you’ve been in contact with an infected person. The location of the encounter with the contact doesn’t matter and should not be recorded. The protocol used that premise to minimize data collection to measuring proximity on the phones only. This also ensured, the application would be useless if people stopped using the app. These principles ideally should lead to better privacy protection. However, when Google and Apple opted for this data minimizing protocol something happened that could not be summarized solely as a win for privacy.”

Privacy to the aid of tech companies

The two big tech companies were enthusiastic about the privacy preserving protocol, Gürses notes. “But for different reasons. It gave them a seat at the table with policymakers and the healthcare sector. Governments, by moving to launch contact tracing apps and given their dominance over 99% of phones, in a sense, summoned Google and Apple to the table. And, Google and Apple came. When they did, they used the privacy preserving protocol to gain an upper hand over public health organizations. This was paradoxical: by applying privacy engineering these companies protected user privacy, but also entrenched the power of these companies vis a vis governments.”

Better guidelines and systems

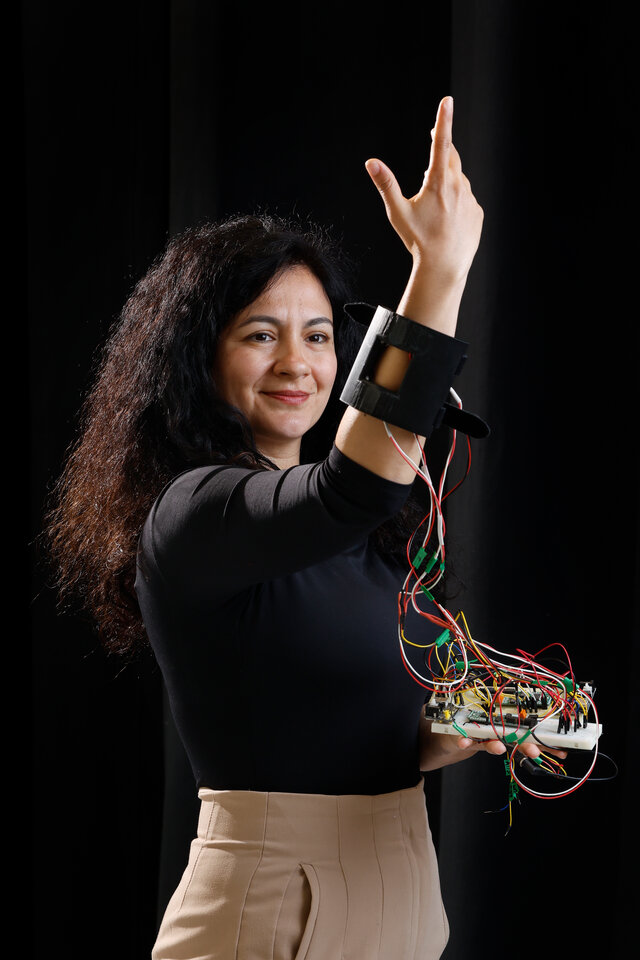

Gürses’ insights provide useful context for Lilika Markatou, cybersecurity researcher at the faculty of Electrical Engineering, Mathematics, and Computer Science, as she works on developing new guidelines and systems. “We can’t expect much from big tech companies when it comes to protecting user privacy. So, we must develop policies and design systems to ensure it happens. This includes stricter privacy protocols and new systems like encrypted databases. That’s what I’m working on – systems that allow data sharing without it falling into the hands of tech companies. The challenge is not only developing these systems but also integrating them into society. Most people are currently fine with their data being stored in the cloud. I hope we all become more aware of the risks.”

Major privacy risks

For Markatou, the work on improved privacy systems is driven by more than just a scientific interest. “I find the technical aspect fascinating, but the subject also touches me personally. I believe everyone has the right to keep their data private and to use technology safely. The idea that someone could read my emails or see my photos is unsettling. Accessing someone's data can also be extremely dangerous, for instance, with personal information that can lead to identity fraud. Sharing information about someone’s sexual or political preferences can also pose significant safety risks.”

Connecting snapshots

While Markatou focuses on innovations, Gürses maps how big tech companies develop new technologies, which is quite challenging. “These companies are huge and operate in the dark, so we have to find ways to capture how they work and whether they comply with regulations. We read white papers they publish, examine their protocols, and check if new tools and services comply with privacy laws. We also look at their history: how have they operated over the past decades? This can provide clues for the future. We collect all these snapshots and try to connect them.”

Informing policymakers and society

Gürses believes it’s her duty as a scientist to inform both policymakers and society about how tech companies operate. “Ultimately, it’s up to the user to make decisions, but people need to be aware of the risks, and they often aren’t as it is hard to track and assess how these giants are evolving. When Google, Apple, Amazon, or Microsoft launch new privacy technologies, we often assume it is a good thing, especially since they can have broad reach. But alarm bells should ring when they introduce these technologies to further concentrate their power. That’s what drives me in my work. By understanding how tech companies instrumentalize privacy laws and technologies, I’ve learned to always look beyond what companies claim to do.”

Reducing dependence on big tech companies

Despite the major challenges, Markatou remains hopeful about finding solutions to limit the power of large companies. “It’s a huge task because we’re still very dependent on these companies in our daily lives. Ask a full room who uses the services of Apple, Google, Amazon, or Microsoft, and everyone will raise their hand. It requires a whole ecosystem of researchers, policymakers, and the industry to initiate change toward a world where our privacy is better protected.”